April 15, 2024

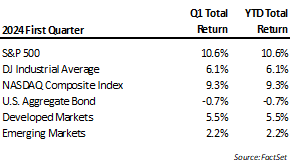

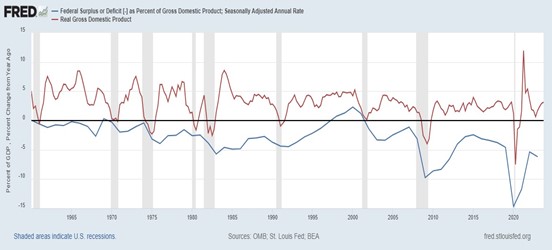

Stocks posted healthy gains in the first quarter, adding to the strong performance experienced in 2023. Continued enthusiasm for AI pushed many tech stocks higher, while optimism for a soft economic landing (slowing inflation without sending the economy into a recession) and interest rate cuts helped broaden the rally to other sectors. In the first quarter, all sectors of the S&P advanced, with the lone exception being REITs, which saw a slight decline of 1.4% (source: Factset). The optimism for rate cuts continued despite economic data and employment trends holding up better than expected, and inflation readings remained stubbornly elevated. However, this data was enough to cool expectations for the magnitude of any rate cuts this year, which pushed interest rates up and resulted in flat to negative performance for many bond indices. Part of the reason growth and inflation remain higher than expected with a 5.5% Federal Funds rate is that fiscal policy continues to be quite stimulative. Long past the disruption and recovery of COVID, the Federal Government continues to run massive deficits (spending more than they take in), with excess spending contributing to economic growth, hiring, and pressure on prices. The magnitude of deficit spending relative to the economy is historically high, and it is pretty unusual to happen this far along in an economic expansion. Effectively, the fiscal spending deficit offsets some or all the restrictive efforts the monetary policy attempts to achieve with higher rates. The chart below shows the Federal Deficit as a percent of GDP (blue line) along with the rate of economic GDP growth (red line). The trend over time is larger realized deficits relative to GDP growth.

Part of the reason growth and inflation remain higher than expected with a 5.5% Federal Funds rate is that fiscal policy continues to be quite stimulative. Long past the disruption and recovery of COVID, the Federal Government continues to run massive deficits (spending more than they take in), with excess spending contributing to economic growth, hiring, and pressure on prices. The magnitude of deficit spending relative to the economy is historically high, and it is pretty unusual to happen this far along in an economic expansion. Effectively, the fiscal spending deficit offsets some or all the restrictive efforts the monetary policy attempts to achieve with higher rates. The chart below shows the Federal Deficit as a percent of GDP (blue line) along with the rate of economic GDP growth (red line). The trend over time is larger realized deficits relative to GDP growth.

In the fourth quarter of last year, the Fed signaled that it thought conditions would be appropriate to start cutting rates. At that time, economic data was more mixed, and inflation readings had receded from their peak in mid-2022. Markets welcomed the news and bid stock and bond prices higher. However, as data in the first quarter started to show growth picking up again and stagnation in better inflation data, questions arose about whether the Fed could justify its plan to cut rates. In policy meetings and public comments this year, the Fed seemingly addressed this issue by indicating they felt there would be sufficient evidence of progress to justify rate cuts still this year. CPI is much lower than in 2022, though the trend has flattened, with readings still well above the Fed’s stated target of 2%. The chart below reflects CPI monthly readings since 2020, annotated with the Fed’s objective in red.

The risk of cutting rates while inflation remains elevated is that it reduces the offsetting effect of running large deficits. Economic growth is likely to be stronger, increasing inflation risk. In our opinion, markets reflected this shift in view during the first quarter through higher stock and commodity prices and lower bond prices, particularly in longer maturities. In periods of elevated inflation, locking capital up at a fixed rate for an extended period (bonds) becomes less appealing versus assets producing income that can change with prices (stocks) and goods with constrained creation (commodities).

In our past discussions of inflation, we noted that the economy could experience multiple waves of inflation, similar to what transpired in the early 1970s. In our opinion, the shifts underway in the fiscal and monetary policy variables increase the probability of that outcome. History supports that thesis. Research published by State Street Global Advisors and Strategas Research Partners examined 62 instances of inflation waves in 24 different countries and found inflation returning in multiple waves to be the more common pattern.

The U.S. inflation experience in the 1970s was at least in part due to the energy supply shock and the resulting sharp increase in oil prices. Currently, several factors at work have the potential to increase inflationary pressure. In the 1990s and early 2000s, economies benefited from globalization, relative peace, and few constraints on commodity supplies, which kept prices for many critical inputs in check. COVID and the deterioration of geopolitical relationships have reversed these trends, and the price of many commodities has been further affected by a long period of underinvestment in new supply.

Rate cuts with this backdrop could further fan inflationary flames, though the Fed seems to be looking for any reason to move forward with a plan to lower rates this year. We think part of the motivation lies with the fast-growing reality of interest expense on government debt. Though we believe they are unlikely to come right out and say it, as interest expense threatens to become the most considerable government outlay, there becomes a solid motivation to manage it. According to research from Bank of America, the run rate interest expense for the Federal Government as of February was $1.1 trillion. If rates are unchanged through year-end, that figure will rise to $1.6 trillion by December. For reference, the largest spending category in Fiscal 2022 was Social Security at $1.2 trillion (source: Congressional Budget Office).

We talk about inflation a lot because it creates a significant risk for savers when it rises. Periods of elevated inflation frequently see the value of financial assets also growing. Still, the issue is whether the gains in price are enough to offset what is lost in future purchasing power. Over long periods, it is easy to think of goods and services that were far cheaper 20, 30, or 50 years ago, though sometimes these changes are overlooked using shorter time references. The quote below is from the management of Dollar Tree stores highlighted in Grant’s Interest Rate Observer and makes one wonder whether the notion of “dollar” stores will soon go the way of the “five & dime.”

“Dollar Tree will add scores of new items to its shelves over the course of 2024 at price tags ranging as high as $7, management announced on its March 13 earnings call. The discount retailer, which imposed a $5 price cap only nine months ago, first “broke the buck” in fall 2021…”

We think there are several things investors can do to protect themselves from inflation, and we have incorporated many of these into our investment strategies. These include minimizing or avoiding long-term, fixed-rate debt, increasing commodity and energy holdings, and investing in companies whose revenues can adjust with inflation faster than the costs necessary to operate the business.

The risks of locking up capital in long-term debt are easy to see. Bondholders that bought too much duration in the world of near-zero percent rates a few years ago are stuck with a tricky proposition. One either has to sell and realize the mark-down loss to carrying value a bond reflects to “adjust” to market rates or hang on to the position and its less productive income stream. In our view, the rates available to savers for locking money up for extended periods (five years and beyond) are better than a couple of years ago but still not that attractive relative to purchasing power risk.

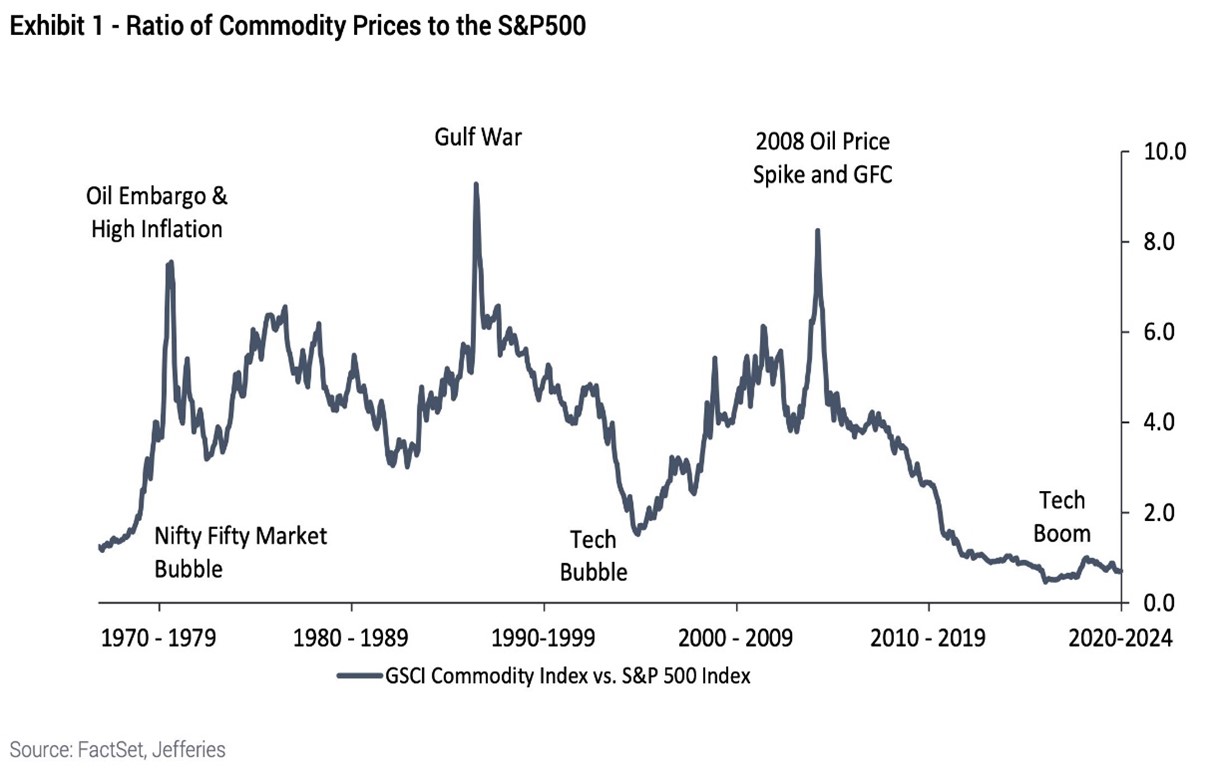

In contrast, commodities, and by extension energy, have shown to be effective assets to offset the impacts of inflation in the past. The inability to create more supply without the investment of capital and labor means the clearing price necessary to supply demand tends to move directionally with inflation forces. That said, not all commodities will move in lockstep with changes in inflation. The level of pre-existing over- or under-supply and the organic growth in demand will influence the magnitude of price change.

However, commodities generally have gone through a long period of underinvestment. The last sustained global boom in commodity demand was in the early 2000s, as China was experiencing rapid growth and making massive investments in infrastructure. Commodity investing during that period was like AI is today; investors couldn’t get enough, and many companies threw money at acquisitions and expansion based on the expectation that demand growth would make it all work out.

It worked well until the Great Financial Crash of 2008 and the subsequent global recession. The resulting fall in demand after a period of aggressive capacity expansion resulted in a lot of excess supply that needed to be digested. Consequently, prices for many commodities fell and remained depressed for several years. Commodities and related companies generated poor returns during the time, and as a result, little capital was sought for investment in the sector.

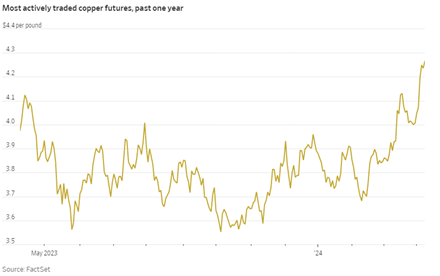

Fast forward to today, markets for many commodities are much tighter, prices are higher, and volatility is often in the form of higher prices. Global conflicts and deteriorating trade relationships exacerbate the effects. So, too, do efforts like pushing renewable energy. Emphasis on renewables results in a higher hurdle rate for investment in “legacy” energy sources while the amount of material – steel, concrete, copper, and rare earth minerals – needed to implement alternative solutions multiplies. Renewable energy initiatives can provide source diversification and environmental benefits, but there is a cost for the transition, and proponents frequently understate the magnitude of the cost. After years of lagging performance, commodities offer attractive relative value to other assets, including stocks.

AI is also cited as a new and significant driver for commodity demand, particularly copper. AI solutions require vast amounts of power, and managing that electricity need makes copper a fundamental part of the equation. Similarly, expanding electric vehicle use, home heat pumps and other battery solutions will necessitate lots of new copper in the infrastructure. Meanwhile, copper has been one of the commodities for which investment in supply hasn’t kept pace with demand. Last year, the refined copper market saw a deficit of 27,000 metric tons, according to the International Copper Study Group. Depending on a specific strategy, we have exposure to copper miners and the metal itself through commodity funds. The chart below shows how copper prices have started to reflect supply imbalance.

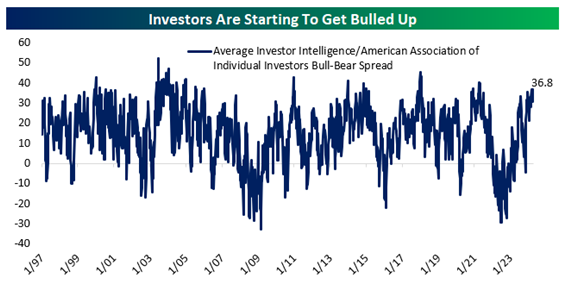

In our opinion, the big move in commodities this year suggests the market is factoring in more inflation risk and that monetary policy isn’t inclined to suppress—consistent with this, interest rates increase, and stocks advance. Broadly, stocks are imperfect inflation hedges, but they offer greater ability than bonds to adjust to rising prices. The significant advance equities enjoyed since October last year extended valuation metrics, resulting in somewhat frothy sentiment. Tactically, given the elevated bullish posture, we think some caution on stocks is warranted. Based on a survey of individual investors, the chart below from Bespoke Investment Research shows the difference between bulls and bears. That difference is at levels where past corrections or consolidations in markets have appeared.

After a steady rise in stocks over the past six months, we think markets will be susceptible to monetary policy actions throughout the balance of this year. Easier policy posture in advance of supporting inflation progress could increase the likelihood of a renewed inflation surge, while tighter policy could result in growth below expectations. If growth slows and inflation remains stubborn, the conversation about the economy could shift to stagflation, a challenging environment for savers. Stagflation, or high inflation and little to no economic growth, could pressure earnings growth and become a headwind for stocks collectively in the upper historical valuation ranges. We expect the Fed to go to great lengths to avoid that risk, particularly leading up to the election.

In assessing current economic growth, earnings reports for the first quarter will be coming out over the next several weeks, and they will provide an up-to-date picture of how demand is holding up and how companies have managed cost pressures. Thus far, the image has been one of resiliency. For Q1 2024, the estimated (year-over-year) earnings growth rate for the S&P 500 is 3.2%, which would mark the third quarter of year-over-year earnings growth for the index (source: Factset). The economy has managed through the rise in interest rates better than expected, and consumers have sustained a higher level of discretionary spending despite having to allocate more income to the rising costs of necessities.

In balancing this spending, however, consumption comes at the expense of savings. According to the Federal Reserve data, the consumer savings rate is now under 4% and in the lowest decile over the past 80 years (source: St. Louis Fed). In the past commentaries, we have highlighted estimates of “excess savings” built up during COVID and forecasts of when this extra capital may become exhausted. We think it is tough to say precisely, but that source of consumer funds is probably no longer material. On the positive side, at least for higher-income earners, savers receive more interest income due to higher rates.

The balance of this year will be pivotal in determining whether our economy will face another wave of inflation. Going back to the Strategas inflation research cited earlier; they found the average period to the beginning of the second wave of inflation was 30 months from the initial peak. CPI in the U.S. peaked in June 2022, putting us about 21 months out from that mark. Though the timing forecast of that research shouldn’t be interpreted as highly precise, this puts the rest of 2024 in that window. Regardless, barring a sudden and sharp rise in inflation this year, we expect the Fed to find enough justifications to cut rates. As long as it is maintained, we believe this expectation will support financial markets. Post-election, we think it is too early to predict how policy and economic activity might trend.

In our opinion, inflation is one of the essential themes investors can track and potentially predict future developments. Meanwhile, the list of unpredictable factors seems only to expand. Hotspots worldwide are multiplying, and the reality is that one headline can change the course of markets very quickly. Add in the dynamics of an election year, and it makes for a stark reminder that plans and forecasts are great until the facts change. If they were to occur, disruptive events come against a landscape where stocks are at the upper end of historical valuation ranges and bond credit spreads are tight. As a result, even as we see supportive factors for markets this year, maintaining healthy diversification and meaningful safety buffers is a prudent strategy. As developments unfold, we will continue communicating any changes in our view and corresponding implications for client allocations. We thank you for your continued trust in us and hope you and your family remain in good health.

Bradley Williams, Chief Investment Officer

Lowe Wealth Advisors

Please remember that past performance may not be indicative of future results. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product (including the investments and/or investment strategies recommended or undertaken by Lowe Wealth Advisors, LLC), or any non-investment related content, referred to directly or indirectly in this newsletter will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated historical performance level(s), be suitable for your portfolio or individual situation or prove successful. Due to various factors, including changing market conditions and/or applicable laws, the content may no longer be reflective of current opinions or positions. Moreover, you should not assume that any discussion or information contained in this newsletter serves as the receipt of, or as a substitute for, personalized investment advice from Lowe Wealth Advisors, LLC. To the extent that a reader has any questions regarding the applicability of any specific issue discussed above to his/her situation, he/she is encouraged to consult with the professional advisor of his/her choosing. Lowe Wealth Advisors, LLC is neither a law firm nor a certified public accounting firm and no portion of the newsletter content should be construed as legal or accounting advice. A copy of the Lowe Wealth Advisors, LLC’s current written disclosure statement discussing our advisory services and fees is available upon request. If you are a Lowe Wealth Advisors, LLC client, please remember to contact Lowe Wealth Advisors, LLC, in writing, if there are any changes in your personal/financial situation or investment objectives to review/evaluating/revising our previous recommendations and/or services.